Interviews with former graduates

The main aspect of my research was a series of interviews with Design School graduates. The aim of the interviews was to understand how students perceive CTS once they leave the university and are working in the industry.

I devised a short semi-structured interview with 4 graduates. The requirements were that they would have graduated from 2021/2022 academic year onwards. This was the year I joined LCC so I could only have the direct experience CTS delivery from that year. Secondly, the students were recommended by other tutors as I didn’t think it would be appropriate to interview students who were in my tutor groups.

I ended up interviewing 4 graduates: 1 student who graduated in 2023/2024 academic year and is currently undertaking an MA; 2 students who graduated in 2022/2023 academic year – one currently in full time employment in a design agency and the other undertaking a paid internship in a famous design agency; one 2021/2022 graduate currently running their own practice and also teaching at LCC. The students were recommended by their CTS3 tutors and I either had their direct contact details or was able to find them on their personal websites.

Each interview lasted for around 30mins and I had prepared five key questions I wanted to ask (and any follow-up questions developed directly from the conversation).

I reached out to graduates via email, explaining the aims of the project and expectations. They were provided with a consent form and transcript of their interview, so that they could decide whether they wanted their data to be shared. All interview data has been anonymised.

Interview questions:

- What is your current role – are you working or studying?

- Did you undertake a DPS year?

- Looking back what was the purpose of CTS within your degree?

- Were there any skills and knowledge that you gained through CTS that are relevant to your current work/study?

- What do you think was good about CTS?

- What could have been better?

Consent form (adapted from the one shared as part of the unit)

Information sheet (email)

Interview transcripts

Primary Research: Analysis and Reflection

The two most revealing findings came from the first two interviews I did with graduates currently working in the industry in junior roles. Both students come from a European background, with English not being their first language, and both in their discussion suggested that they were CTS ‘converts’ – i.e. they weren’t naturally inclined towards academic writing or research, but found their voice, positionality and interests in CTS in their final year. The first respondent said: “You start with something that is hard for us [designers], something out of our element so… But you have the possibility of learning so much, so many subjects, it was so interesting.”

This suggests a couple of things: firstly, that students clearly appreciate the opportunity of developing an in-depth research project on a topic of their choice; secondly that the positioning of CTS in year 1 and year 2 needs to emphasise both a closer connection to individual courses, while also giving students greater choice over their learning journey.

While all four graduates I interviewed got high grades, none of them particularly mentioned writing as a skill they enjoyed, or found relevant or useful in their current role. Rather, their understanding of the value of CTS was more related to less tangible, transferrable skills and more of an ‘attitude’ to the world around them. For example, the first interviewee said: “One of the best things about CTS was that someone gave us, was that you had to question everything and make your opinion out of it. Researching was very intriguing to me.” This suggests that the value of CTS resides in nurturing a critical voice and allowing students to see different avenues for research and discovery. Another respondent also commented that they saw CTS being essential in developing the students’ critical skills which is increasingly important in a world of AI and misinformation.

Still, CTS also allowed them to develop some practical skills in terms of research: “And now that that you ask me about it and now that I thought about it, a lot of like, how I look for things and like, how even I ask ChatGPT, it’s about… I learned at CTS to do this thing. But I don’t necessarily think of it as like, oh, I learned this specific thing from CTS. It’s more about like how I view the world.” The same respondent also acknowledged the pleasure of in depth research: “and I think it was also one of the only moments in my life when I actually had to do this sort of research like deep research inquiry, that like, right now, we’re kind of we don’t have that much time for research. We don’t have time to think about what this all means and how this all, like we do fast research and design. And it was nice to go deep, but still within kind of a subject that I wanted.”

Both interviewees also confirmed a long-lasting legacy of CTS in terms of what they do outside of work, suggesting that CTS encouraged them to be more open and curious about the cultural landscape: “Daily, I research, read articles, exhibitions, I am curious and want to go and see stuff”; while the other respondent said similarly about discovering a publication in their final year: “when I was doing my dissertation and I’m still reading their articles like there are things that have been embedded in the way I work and the resources I read and the materials that I use.”

Finally, in the context of the industry, the second respondent spoke very eloquently that it was hard to quantify the impact or value of CTS as ‘it’s not something you can put on your CV”, but recognised that it was absolutely essential in being able to have a conversation with clients or colleagues in the studio, positioning their projects in a historical or cultural context : “it’s about kind of knowing what periods are like and how design is seen in the world and stuff like that which is kind of again the more niche things that you don’t necessarily need when you’re applying for jobs but are kind of very essential when you’re actually doing like real work with like real clients. […] it’s about a lot about how you kind of relate and like refer to things. So when someone says I don’t like this logo, it looks modernist or […] or how you refer to like seeing art and like observing and like commenting on art. It’s more about in meetings I’d say. Like understanding what you’re working on, on a deeper level, then per se, like writing or…”

This seems to confirm my original hunch that while students may not be able to see or recognise the value of CTS ‘in the moment’, they are able to see its impact when working in the industry. They offer a holistic interpretation of the design professional: not just the skills, taste or approach of a designer, but a critical practitioner – whose ‘intuitive’ actions, as Jenny Rintoul writes, are really an articulation of deep experience and knowledge. Some of that knowledge and experience, then, surely also comes from CTS.

Research Methods: Secondary Research Reflection

At the start of the project, I was not sure what methods might be best suited to my research. I originally considered working with my third year students, trying to experiment in class and getting their feedback on how writing can be used as a form of liberatory practice. However, after some reflection, my focus shifted to interviewing graduates. This choice was made for several reasons, not least because I thought it allowed me to get a bit more critical distance and to get responses that look into the impact of CTS from a more long-term perspective (this is something that Stefan Collini discusses in his text cited in the Secondary Research section). In a fast-paced university environment, when feedback and action often follow short cycles, taking a longer view and engaging in research with former students who had some critical distance from their educational experience, seemed like an interesting approach. It also allows me to sidestep some of the ethical questions around researching with and ‘on’ my students whose work I will be marking at the end of the unit.

As a result, I did some reading around interviews as a research method. I had done interviews as part of my PhD, but these were mostly ‘oral history’ interviews conducted with post-war designers at the end of their careers. As such, these semi-structured interviews ended up as ‘hagiographies’ – I was trying to capture their life story, setting it in the particular historical and disciplinary context – but was not probing for a particular reflection on an issue. While I enjoyed doing these interviews as it gave me an opportunity to understand an intimate view of a designer’s journey and a perspective on the wider industry of the time, I found them of limited value as ‘research data’ and, indeed, did not end up using them in my final dissertation.

I was, therefore, a bit sceptical of interviews in this case. I do not want them to turn into meandering exercises with little value. As a result, I decided to keep them quite concise and focused, with a limited series of questions, that would still allow for enough scope for follow-ups. I started with a long list of possible questions, reducing them to five key questions to guide the conversation. I though that a semi-structured format would be best suited to allow scope for my interviewees to develop a narrative around their own experience.

To inform my approach, I read a few suggested sources about interviews. Mats Alvesson’s text was useful in offering a framework for thinking about interviews as an active process of the construction of meaning – the idea that interpretation didn’t happen post-interview but that it started from the moment of the interview itself. This fit into what he described as the romantic view of interviews – resisting the idea of a positivist universal truth. The idea that interviews may offer the opportunity to “engage in a ’real’ conversation with ‘give and take’ and ‘empatic understanding” (Alvesson, 2016, p.6) appeals to me as a way of treating interviewees – in this case former students – as equals – something that is not always there in a tutor/student relationship.

Further, I also read Irvine, Drew and Sainsbury’s text on face-to-face vs. telephone interviews. While speaking to students via Teams (or other online platforms) seemed like the most efficient and obvious choice, the text also emphasised the importance of including visual clues as part of the analysis. While I think of my interviews as ‘fact-finding’ missions – if personal, individual opinions can be deemed as ‘facts’ – this also nudged me to think about how this visual information may provide ‘the interviewer with a lot of extra information that can be added to the verbal answer of the interview’ (Irvine et.al., 2012, 90). While I understand that for some research projects this non-verbal, visual, tactile or other cues might be more relevant, I am not sure how and in what way they might shape my own project. Nevertheless, this has reminded me that I should take notes about the interview process itself, rather than just notes about what was said, perhaps approaching the interview as a kind of visual ethnography.

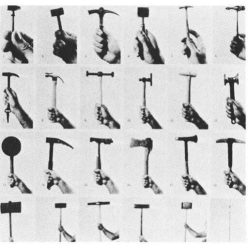

Figure: Drawing from Michael Taussig’s “I Swear I Saw This”

One of my favourite texts to give to students is Michael Taussig’s I Swear I Saw This, so perhaps this is an opportunity to also incorporate some of his thinking into my interpretation of the interviews. For example, should I sketch, use visual documentation? And what kind of ‘truth’ or ‘witnessing’ of the interview might this offer? Will it give me anything other than a nice illustration to go along with the transcript? As Taussig, writes, “drawing intervenes in the reckoning of reality in ways that writing and photography do not” (Taussig, 2011, p.22). So could there be any value in drawing as an analytical tool for my analysis, at least to get beyond some preconceptions I might have about what I might ‘find out’? Perhaps this is a valuable thought experiment, even if it doesn’t generate any meaningful outcomes at the end.

Soft Data: a reflection on the interview process

Giorgia Lupi, ‘soft data’ infographic, 2018

Following our third workshop, my tutor suggested writing a post about the ‘experience’ of the interviews. In the workshop, we discussed Rick Harris’s An Eye for Detail – The Tyranny of the Transcript, which suggest that the interview is much more than it’s transcript.The author is nudging researchers to capture the ‘soft’ information that exists beyond the verbal transcript – the feelings, ambience, sounds, smells, etc. that inform the experience of the interview and therefore may also shape its outcomes. More importantly, this data may also shape the interview’s analytical interpretation. This also may relate to what Alvisson (2012) calls the ‘localist’ approach to interviews. So below is an outline of what my interviews ‘felt’ like.

I conducted four different interviews and each experience was slightly different. They were conducted over a fairly long time-frame – around 6 weeks or so – as this depended on my interviewees’ availability. This allowed me to ‘practice’ the interview process itself: in some ways I think I got ‘better’ at interviewing or getting at the ‘root of the problem’ of what I was trying to investigate with each interview. (Perhaps my ARP question should have been around how to do interviews )

The first interview I conducted was the one I reflected on in the workshop. It was conducted at the end of the workday. My respondent works in a design agency and I interviewed them while they were still in the office. It was the end of the week, so the interview was set in a noisy environment as people were leaving the office, saying goodbye to each-other before the weekend. While both me and the interviewee were wearing headphones, I could sense that they were perfectly aware of their environment. They knew that their work colleagues were overhearing their conversation and I do think this may have shaped how they approached the interview and the answers they gave. As the interview went on, their colleagues were slightly interrupting the conversation. It made me also self-aware: I kind of wanted to get my questions out and get it done. Despite the answers they interviewee provided, which were really interested, informative and gave me a lot of scope for reflection, I did not enjoy the interview process at all. This only goes to show how the logistics of research determine what kind of knowledge can be discovered/generated. Perhaps being able to conduct the interview in a quieter, more intimate setting would have provided me with different outcome. While I don’t necessarily embrace the total relativism – I do think some answers I got would have been given in any other context – it does mean that I want to be careful about drawing any kind of broad-reaching conclusions from these interviews.

This reflection also reminded me of the data visualisation specialist Giorgia Lupi’s notion of soft data and the possibility or impossibility of capturing that kind of data: “Information design is often based around hard numbers and supposedly irrefutable facts. Soft data, on the other hand, has fuzzier, less quantifiable edges. It’s concerned less about the number itself than it is about the human context around numbers.” (Stinson, 2018) Lupi tries to translate this soft data into visual outcomes – making visible something that might otherwise pass unnoticed without necessarily offering a particular interpretation or judgement on it, and yet still generating meaning out of it.

Below is a link to an interesting article about a project that draws on such ‘soft data’:

https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/how-kaki-king-and-giorgia-lupi-used-data-to-make-sense-of-a-childs-illness/

Secondary Data

Informed by the reading of Helen Kara’s Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences which was set for our third workshop, I decided to review NSS data available through UAL’s dashboards. In particular, I focused on free text comments to see if students referred to CTS in their feedback. This data would allow me to get an understanding of the students’ perception of CTS during their studies, which could then be compared to the perception of CTS following their graduation.

Hara cautions that “Some may fear that” secondary data “would feel too clinical or distant if they didn’t have intimate personal knowledge of the context in which the data was gathered.” (p.104). And indeed, this may be the experience of sifting through NSS data which is standardised and gathered by courses and for courses.

I looked through NSS free text comments for 2023/2024 and 2022/2023 academic year for all 8 UG courses in the Design School. I gathered comments that directly mentioned CTS, but also comments that referred to theory, history, critical thinking, academic learning, lectures, or similar keywords that may ostensively be understood to be related to CTS.

As CTS if often perceived by students to sit outside their course and is organisationally removed from course structures, some of the comments in the survey were more difficult to interpret for me than, perhaps, they would be for course leaders who have intimate knowledge of the whole course delivery.

It was also often difficult to gauge whether students were referring to CTS or any other unit on the course when this wasn’t explicitly mentioned. For example, one respondent said they appreciated having ‘loads of freedom in the choice of topics and mediums one works with’. The comment about topics, for example, could refer to CTS3, the dissertation unit, where students choose their own topic of research, but it may also refer to course units where students choose their own briefs, for example. It is impossible to know this because of the way the data is collected.

More broadly, what is noticeable from the data gathered is the lack of reference to CTS, writing, history or theory within NSS data.

In the 2023/2024 academic year, out of a total of 207 responses for all Design School courses, only 13 responses made reference to CTS either directly or by mentioning theory, history, critical thinking or similar concepts.

Similarly, in 2022/2023 data, out of 177 responses, only 19 made reference to CTS-related content.

This can be seen to further reinforce the idea that CTS is marginalised within the current structure. It also reflects the lack of involvement of CTS lecturers in NSS data gathering – for example, we aren’t there during ‘pizza survey parties’ to nudge students to comment on CTS in the same way that course tutors are. While this, on the one hand, perhaps reflects more truthfully the students’ perception and positionality of CTS in the curriculum, it also highlights the limitations of working with secondary data, as cautioned by Hara.

What else did the data reveal?

The whole data is available at the PDF attached below.

Overall, the comments fall into two main categories:

- negative feedback from students who found CTS unsatisfactory either because of its organisation, individual tutor’s teaching approach or because they found it to be boring/irrelevant to their studies.

Here are a few comments in this category:

“During third year, the way in which the dissertation and the final project are organised is very poor. The overlapping of the two makes it difficult to accomplish both projects well. I was not able to finish writing my dissertation due to this.”

“The CTS course is extremely biased and non-conclusive to the brief. Feedback and marking is largely contradicting the tutorials done with professors. The criteria marking are inconsistent with the final feedback. The CTS course should be reassessed and re-evaluated as it is largely effective for one’s final grade. The subjects explored in this unit are either done on the subjects that students would like to explore or the subjects of which the tutors would like to hear/read about; it is never both.”

“Not much support for CTS, very independent which I think would’ve been difficult for international students whose first language isn’t English and/or haven’t studied these theories or topic before.”

“In terms of CTS, from the moment I joined UAL it has been awful. Lack of communication and the disconnect from the studio practice.” - students who highlighted the gulf between the emphasis on technical competency and overall lack of theory/academic underpinning of their course. Some comments here included the following:

“We definitely didn’t have any theoretical lessons, which made the course feel like we could do anything without making much sense, mostly if they are supposed to be preparing you to face the outside industry world. It is a shame since the projects are exciting, but there is no base or no logic to sustain all of it. […] There is no reading list or encouragement to do so. All were very independent and figuring things ourselves.”

“the course gives no historical, cultural or theoretical classes regarding the topic of study. It only encourages experimentation and curiosity, which, although extremely important and appreciated, do not serve to give a complete picture of the study.”

“Lacking a bit in specific theory. It has been replaced with practice, but it gets a bit repetitive”

“There is not enough theory provided.”

“There is a huge gap in technical learning and theory.”

“Not enough examples and references supporting and helping understand the theoretical and academic knowledge.”