Object-based teaching is at the core of Contextual and Theoretical Studies delivery in the Design School at LCC where I work. We use objects – whether physical ones or images – as a way of engaging undergraduate students in conversations around complex topics such as design canon, identity, media cultures, decolonisation, climate crisis, etc. In my seminars with students, I often ask them to bring objects that are meaningful to them, using them as the starting point of contextual and theoretical enquiry.

For the micro-teaching session, I considered two different approaches: one more structured and the other one more open-ended. The first approach was to bring a range of different objects and ask students (colleagues) to organise them based on the objects’ perceived sustainability. The aim was to reflect on the way sustainability is communicated through an object’s design: its colours, materials, graphics, intended use etc. However, I opted against this approach as it seemed the time available would not be sufficient for meaningful discussion.

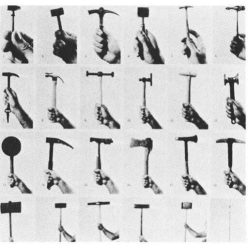

I therefore opted for a second approach that I called ‘Making meaning’. This included bringing a range of objects, asking each person in the session to choose one and providing them with a worksheet to guide their engagement with the object: from the initial description of its materiality, to developing a more in-depth critical reading of its wider social, cultural, political, economic meaning. I selected a range of objects I had at home, with the only guiding rule being that they had to be made of different materials. None of the objects had a particular personal meaning to me.

I set up the activity with a short power-point that included the aims of the session and a few references: Sherry Turkle’s book ‘Evocative Objects’ was key for the way it uses objects as ‘tools to think with’; and Jane Rendell’s text ‘The Welsh Dresser’ for its unique writing style and the way it uses personal objects as entry points for wider discussions about culture, politics and gender. This session structure very much mirrors what I might normally do with my students, so one of the aims for me was to get a better understanding of it from a student’s perspective: Is it engaging? What do they get out of it? Does it support critical thinking?

My colleagues seemed engaged with the activity from the start: setting the objects on the table and having them all explore the items together before picking out one they wanted to analyse. It made the session feel very ‘active’ as they circled around the table to review all objects. The task was very open-ended, allowing everyone to bring their own knowledge, identity and personal history to the task. After giving them the worksheet and getting everyone to work independently for about 10mins responding to the prompts on it, we discussed each individual object. They all brought interesting observations about the objects’ materiality, their perceived use and wider cultural meanings. My colleagues commented that they found the worksheet really useful and that I should give it more value by giving it a title and labelling this approach more clearly (this comment came from a colleague working in the museum at CSM). This aspect was also highlighted by my tutor in the written feedback I got: “In handing out sheets that supported participants associative thinking and emotion of chosen objects, the session was enhanced even further.”

While in my teaching I normally ask students to bring objects and they work on their objects individually, I really appreciated the approach of having students work all on the same objects. Two of the colleagues in the session gave us one objects that we all had to analyse together, rather than each person choosing a different object (which is normally my approach). This made our discussion around the object focused and it really emphasised peer learning through exchange of ideas. This is an approach I will certainly adopt with my students going forward.

References: Turkle, S. ed. (2011) Evocative Objects: Things we think with. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Rendell, J. (2010) Site-Writing: The Architecture of Art Criticism. London: I.B. Tauris.