3. Assessing Learning and Exchanging Feedback

The elephant in the room: AI and writing in creative practice

Contextual Background

Contextual and Theoretical Studies units in the Design School at LCC are assessed mostly through writing. Students submit essays, reviews, reflections on practice, dissertations – different forms of writing depending on their level of study – that are used to assess their learning in CTS units (mostly focusing on Knowledge, Enquiry and Communication as criteria). Plagiarism has always been an issue in assessing written work, but the ease of access to tools such as ChatGPT has led to writing as a form of assessment coming under a lot of scrutiny, especially in an art and design context.

Evaluation

The main problem of AI-generated work is not the fact that students use it to ‘write for them’, but the fact that they miss on the learning that comes through independent research, reading and thinking (UCL, n.d.). This poses the question about the value of writing as a form of assessment: Why are we using it? What is being assessed? What kind of writing are we assessing? How does this support students’ diverse needs? The wide availability of large language models, therefore, calls for a reconsideration of how students are able to evidence their learning and demonstrate they are meeting the learning outcomes. While I think the introduction of AI has led to an unnecessary ‘demonisation’ of writing in creative education (I have sat through many meetings that identified writing as an obstacle to attainment), it is important to reflect on the role of writing in the context of assessment.

Contextual Studies vs Writing

Since joining LCC as Contextual and Theoretical Studies lead in 2021 I have tried to move away from identifying CTS with ‘writing’. Although most of our assessment formats take written form, CTS is not about ‘writing’. We do not teach students ‘how to write’; it is not a creative writing programme. Rather, we want to engage students in situating their practice in the wider social, cultural, political, economic or historical context. We want them to critically reflect on art and design as a meaningful force in our social and political lives. So the question becomes of how can we facilitate students’ engagement with CTS without having them obsess over writing? How can they engage in the process of research/reading/discovery without being intimidated by the written submission that comes at the end of that process?

Moving Forwards

Visualising research

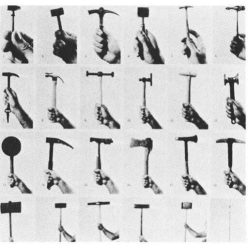

The first step might be to help students see CTS as the process of research/thinking/reflection/reading. Therefore, to start their CTS journey in year 1 with assessment formats where writing is secondary to other forms of knowledge production: visualisation, mapping, recording, listening etc. Students will be asked to produce journals where they document their research in a more visual, reflective, intuitive way – validating forms of knowledge that don’t take a ‘traditional’ academic form.

This will also allow the CTS team to sidestep the AI challenge: we will not be assessing a final ‘written’ piece of work as evidence of the student’s learning, but will be able to assess their research journey to as evidence of their knowledge, enquiry and communication skills (Sharples, 2023).

Introduce different submission formats

As part of a broader revalidation in the Design School, I have expanded the submission formats beyond essay writing. This will include annotated bibliographies, live presentations, research journals, and process documents. We might also consider other formats such as exhibition proposals or videos, for example, instead of final-year dissertations to facilitate different ways of communicating knowledge that brings together visual and written skills. This is to cater to different learning needs, but also to emphasise different forms of knowledge production in design education.

Ethics of AI as method

Rather than demonising AI, I also aim to open a discussion about the ethics of AI use from an environmental, social and cultural perspective, asking students questions about what kind of knowledge is being produced, how and for whom? These questions might open up a more inclusive and critical discussion about AI and we can reflect, as a group, what it actually means to use AI: what impact it has on the environment, for example, or what it means when it reproduced racial biases, for example. While this may not prevent the students who are pressed for time from using it, it might open a more honest discussion about the way AI may be used creatively and responsibly.

References

Engaging with AI in your education and assessment. University College London. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/students/exams-and-assessments/assessment-success-guide/engaging-ai-your-education-and-assessment

Porsdam Mann, S., Earp, B.D., Nyholm, S. et al. (2023) Generative AI entails a credit–blame asymmetry. Nat Mach Intell 5, 472–475

Sharples, M. (2023) Towards Social Generative AI for Education: Theory, Practices and Ethics. Learning: Research and Practice, Vol 9 (2), pp.159-167.

Xia F., Stinckwich S. (2023) “On the Unsustainability of ChatGPT: Impact of Large Language Models on the Sustainable Development Goals,” UNU Macau (blog). Available at: https://unu.edu/macau/blog-post/unsustainability-chatgpt-impact-large-language-models-sustainable-development-goals.